This article has been translated from Chinese by ChatGPT, and the wording may not be entirely accurate.

Section GC Analysis - Part 3 Reference Construction Process

Overview

This article is part of the Addressing Linux Kernel Section GC Failure Issues series.

- Section GC Analysis - Part 1 Introduction to the Principle

- Section GC Analysis - Part 2 Gold Source Code Analysis

- Section GC Analysis - Part 3 Reference Construction Process

- Addressing Linux Kernel Section GC Failure Issues - Part 1

- Addressing Linux Kernel Section GC Failure Issues - Part 2

In the previous article, we introduced the process by which the gold linker deletes unused sections after the --gc-sections option is enabled.

In this article, we will explore the process of establishing references by linkers, combining the source code of the ld.bfd linker (the default ld).

Preparation

Download the Source Code

wget https://ftp.gnu.org/gnu/binutils/binutils-2.40.tar.gz

tar xvf binutils-2.40.tar.gz

cd binutils-2.40/

Or clone the binutils repository:

git clone https://mirrors.tuna.tsinghua.edu.cn/git/binutils-gdb.git

Compilation

make all-ld -j

The compiled ld.bfd linker is located in ld/ld-new.

Setting Up a Debugging Environment

Write a test program test.c:

int fun1()

{

return 0;

}

int fun2()

{

return 0;

}

int un_used(){

return 0;

}

int main(){

fun1();

fun2();

return 0;

}

fun1() and fun2() are both called by main() and thus should be retained during the GC process; the un_used() function is not used and should be deleted in the GC process.

As in the previous article, we write a configuration file that allows us to debug directly in VSCode. Refer to the previous article for how to use it.

{

"version": "0.2.0",

"configurations": [

{

"name": "GDB BFD",

"type": "cppdbg",

"request": "launch",

"program": "${workspaceFolder}/ld/ld-new",

"args": [

"--gc-sections",

"-dynamic-linker",

"/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2",

"-pie",

"/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/13.1.1/../../../../lib/Scrt1.o",

"/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/13.1.1/../../../../lib/crti.o",

"/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/13.1.1/crtbeginS.o",

"-L/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/13.1.1",

"-L/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/13.1.1/../../../../lib",

"-L/lib/../lib",

"-L/usr/lib/../lib",

"-L/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/13.1.1/../../..",

"test.o",

"-lgcc_s",

"-lc",

"-lgcc",

"/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/13.1.1/crtendS.o",

"/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu/13.1.1/../../../../lib/crtn.o"

],

"cwd": "${workspaceFolder}",

"setupCommands": [

{

"description": "Enable pretty-printing for gdb",

"text": "-enable-pretty-printing"

}

],

"stopAtEntry": false

}

]

}

Terminology Explanation

-

Symbol: A symbol typically refers to the name of a variable or function. For example, in C, when a function or a variable is declared, the compiler saves their names as symbols. The symbol table is a data structure that contains all symbols and their related information, which the linker uses to find and resolve references.

-

Relocation: During the compilation and linking process, relocation is an essential step. The compiler does not know the final position in memory of each symbol when compiling the source code. Thus, the object files produced by the compiler will include placeholders that need to be filled with the actual addresses during the linking process; these placeholders need relocation. For instance, if a function calls another function, the compiler may not know the actual address of the called function in memory, so it generates a placeholder. The linker then finds the actual address of the called function and replaces the placeholder during linking, completing the relocation.

-

Relocation Entry: When the assembler encounters a reference to a target with an unknown final position, it generates a relocation entry, instructing the linker on how to modify this reference when merging the object files into an executable.

typedef struct { Elf64_Addr r_offset; // Section offset where the reference that needs modification is located. Elf64_Xword r_info; // Stores the symbol table index and relocation type. Elf64_Sxword r_addend; } Elf64_Rela;

Function Call Chain Analysis

The _bfd_elf_gc_mark() function in elflink.c is obviously used to mark sections that have been used.

bool

_bfd_elf_gc_mark (struct bfd_link_info *info,

asection *sec,

elf_gc_mark_hook_fn gc_mark_hook)

{

bool ret;

asection *group_sec, *eh_frame;

sec->gc_mark = 1;

/* Mark all the sections in the group. */

group_sec = elf_section_data (sec)->next_in_group;

if (group_sec && !group_sec->gc_mark)

if (!_bfd_elf_gc_mark (info, group_sec, gc_mark_hook))

return false;

/* Look through the section relocs. */

ret = true;

eh_frame = elf_eh_frame_section (sec->owner);

if ((sec->flags & SEC_RELOC) != 0

&& sec->reloc_count > 0

&& sec != eh_frame)

{

struct elf_reloc_cookie cookie;

if (!init_reloc_cookie_for_section (&cookie, info, sec))

ret = false;

else

{

for (; cookie.rel < cookie.relend; cookie.rel++)

if (!_bfd_elf_gc_mark_reloc (info, sec, gc_mark_hook, &cookie))

{

ret = false;

break;

}

fini_reloc_cookie_for_section (&cookie, sec);

}

}

if (ret && eh_frame && elf_fde_list (sec))

{

struct elf_reloc_cookie cookie;

if (!init_reloc_cookie_for_section (&cookie, info, eh_frame))

ret = false;

else

{

if (!_bfd_elf_gc_mark_fdes (info, sec, eh_frame,

gc_mark_hook, &cookie))

ret = false;

fini_reloc_cookie_for_section (&cookie, eh_frame);

}

}

eh_frame = elf_section_eh_frame_entry (sec);

if (ret && eh_frame && !eh_frame->gc_mark)

if (!_bfd_elf_gc_mark (info, eh_frame, gc_mark_hook))

ret = false;

return ret;

}

Let’s not concern ourselves with its logic for now and instead, look at its call chain.

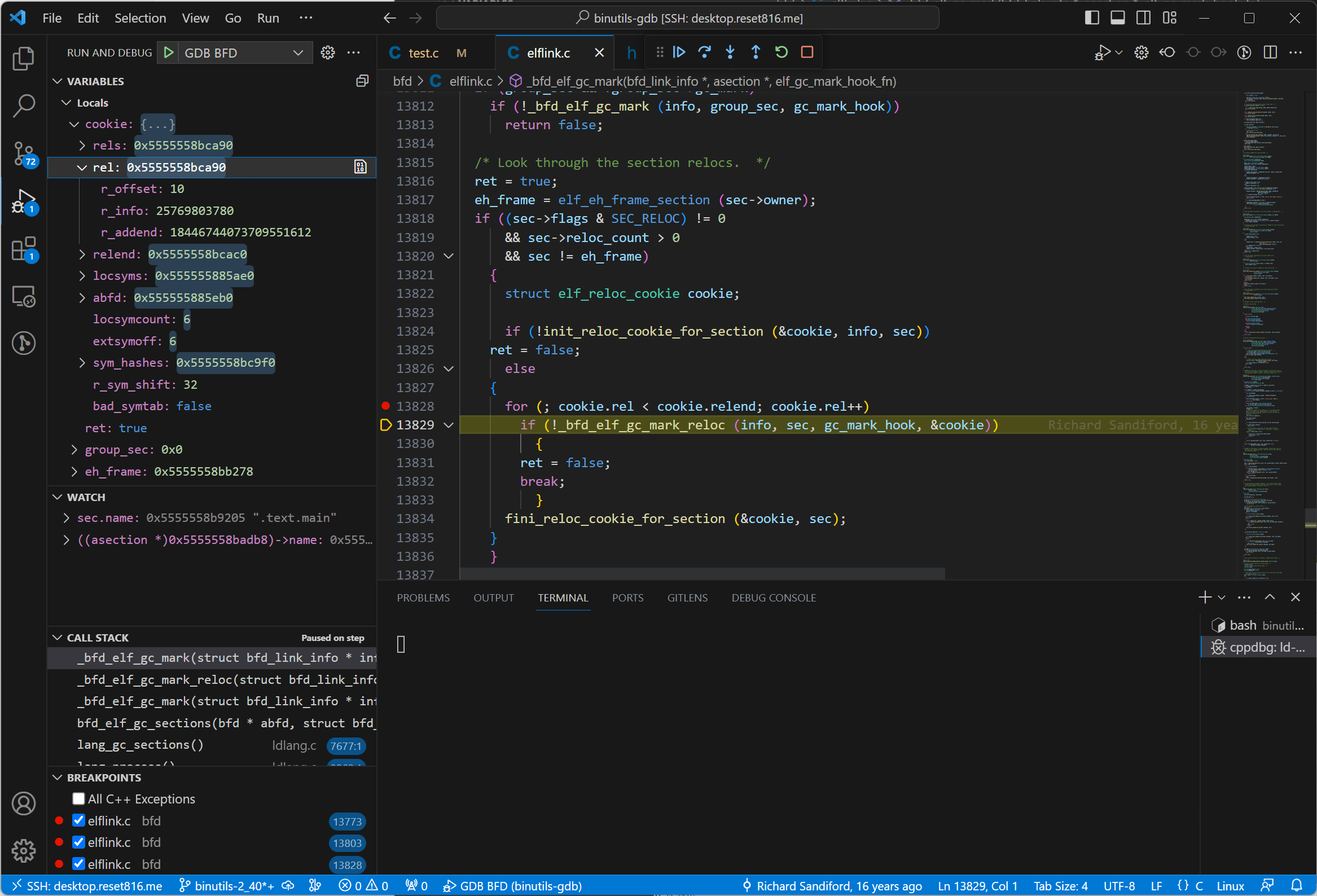

Place a breakpoint at this function and continue until sec.name is .text.main.

As we can see in the call stack, there are two _bfd_elf_gc_mark() frames in the stack, with r_offset being 10.

If we continue running at line 13829 and enter the _bfd_elf_gc_mark_reloc() function, this function will call _bfd_elf_gc_mark() again.

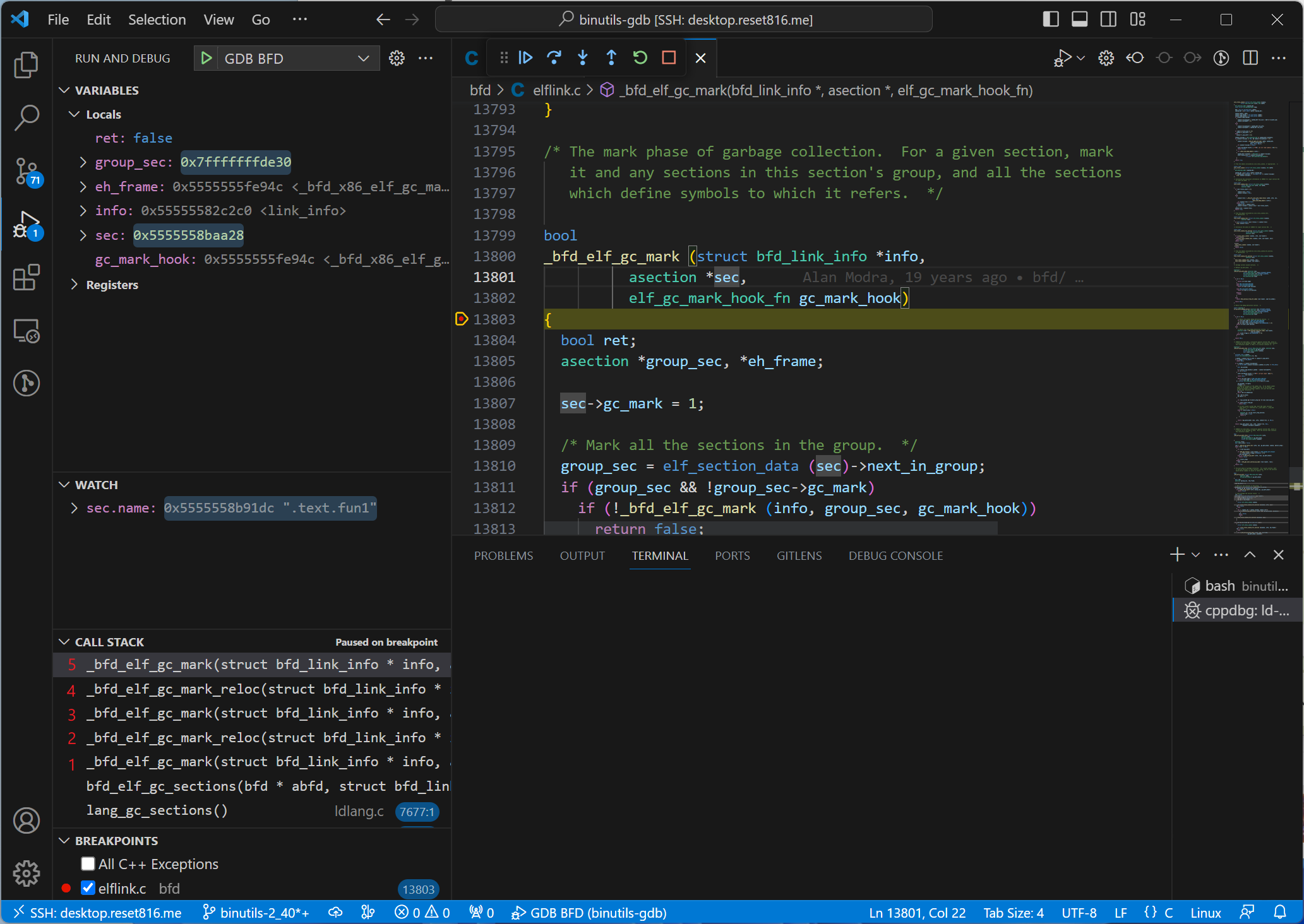

This adds two more frames to the stack, creating a total of three _bfd_elf_gc_mark() frames. Clicking on Call Stack Items allows us to switch between different stack frames and inspect their values.

frame |

sec.name |

|---|---|

frame 5 |

.text.fun1 |

frame 3 |

.text.main |

frame 1 |

.text |

The table above shows the value of sec.name in different frames, indicating the section name currently being processed by that frame. It implies that the stack is now handling .text.fun1.

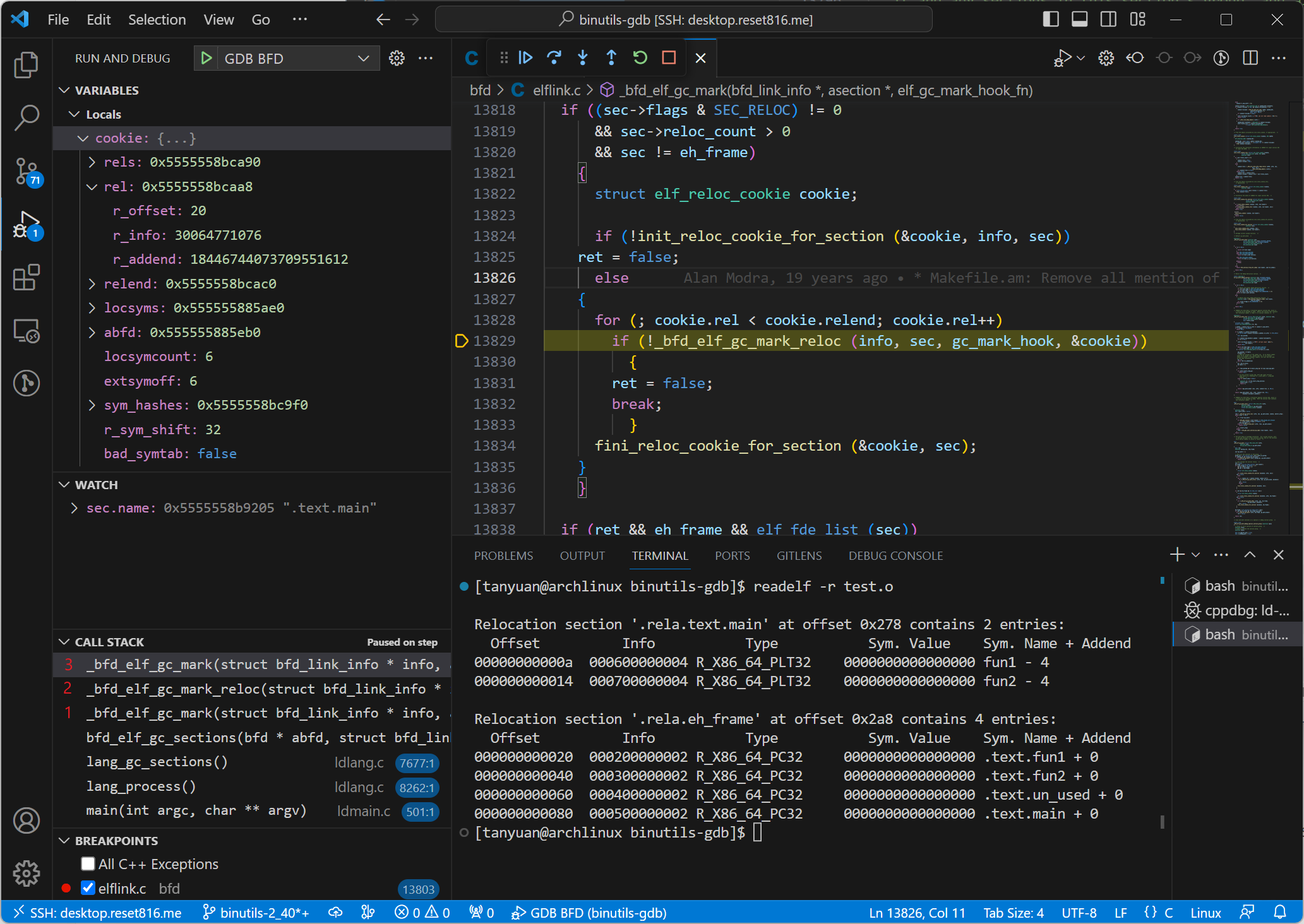

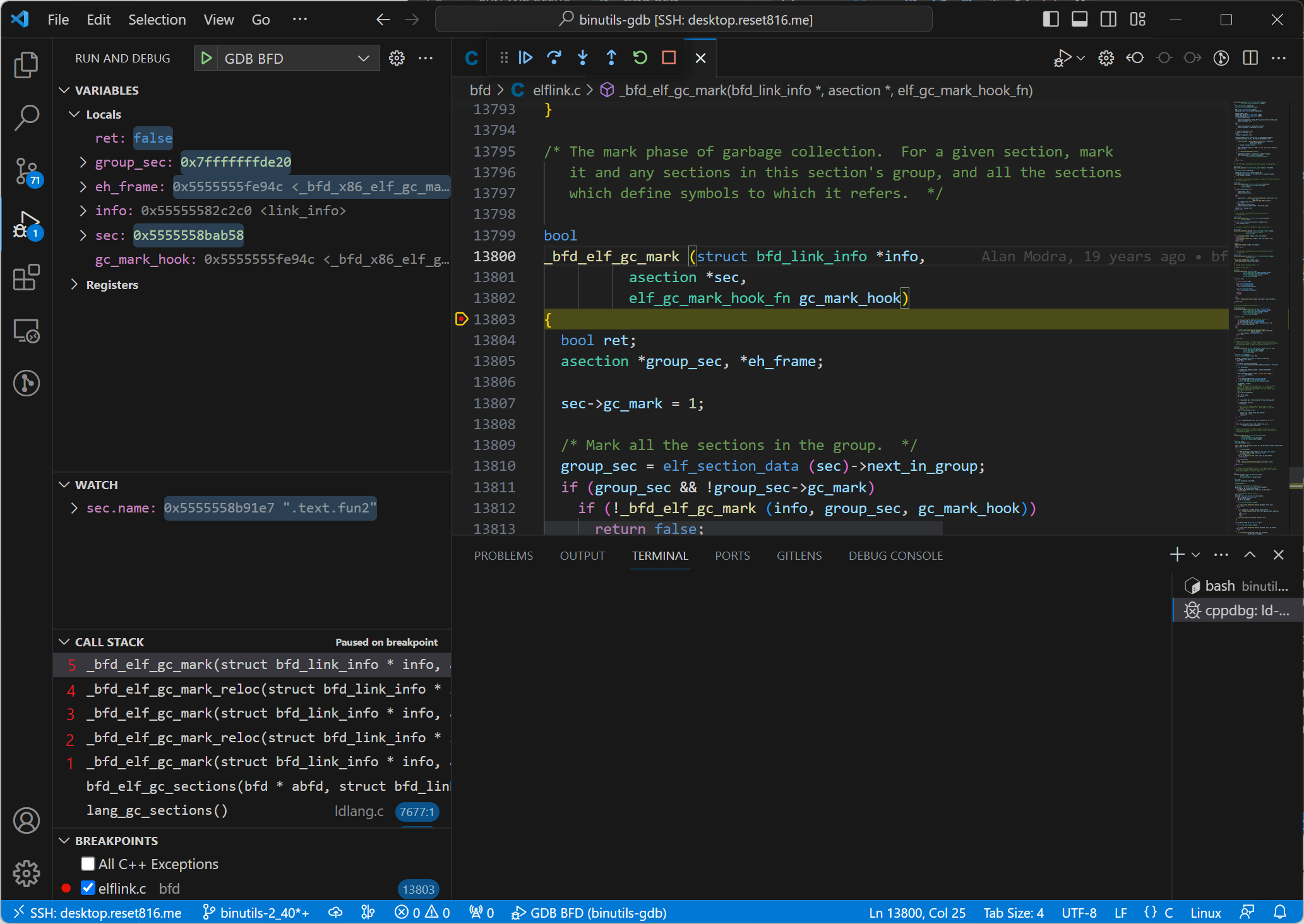

After ‘frame 5’ and ‘frame 4’ have finished executing and returned to ‘frame 3’, the for-loop cookie.rel is incremented, starting the iteration of the next reference in .text.main. From the image above, we can see that this reference entry has an r_offset of 20. Calling _bfd_elf_gc_mark_reloc() here, the function will call _bfd_elf_gc_mark() to process this reference again, pushing new frames and re-establishing ‘frame 4’ and ‘frame 5’.

The table below shows the state of the current call stack after re-establishing ‘frame 5’. Compared to the previous table, this time ‘frame 5’s sec.name value is .text.fun2.

frame |

sec.name |

|---|---|

frame 5 |

.text.fun2 |

frame 3 |

.text.main |

frame 1 |

.text |

From this, we can infer that this is the recursion of scanning section references to other sections, which means, when scanning a section, the section’s gc_mark is set to 1, and then the references of the section are iteratively processed (pushing the call stack) until the stack is empty, and the for-loop is fully executed, only then the scanning of that section is finished.

Data Structures and Code Analysis

The process of iterating over references to other sections by the current section is accomplished by this piece of code in _bfd_elf_gc_mark():

for (; cookie.rel < cookie.relend; cookie.rel++)

if (!_bfd_elf_gc_mark_reloc (info, sec, gc_mark_hook, &cookie))

{

ret = false;

break;

}

_bfd_elf_gc_mark() function will call the _bfd_elf_gc_mark_reloc() function…

Here, the type of cookie is elf_reloc_cookie:

struct elf_reloc_cookie { Elf_Internal_Rela *rels, *rel, *relend; // Represents relocation entries in the ELF file. Indicates the start, end, and currently processed relocation entries in the relocation entries array. Elf_Internal_Sym *locsyms; // Local symbol table in the ELF file. bfd *abfd; size_t locsymcount; size_t extsymoff; struct elf_link_hash_entry **sym_hashes; int r_sym_shift; bool bad_symtab; };

So, the purpose of this loop is to iterate over all the relocation entries (from cookie.rel to cookie.relend). In each iteration, the _bfd_elf_gc_mark_reloc function is called to process the current relocation entry.

The following table is the stack when processing .text.fun2:

frame |

Function Called | Object Handled |

|---|---|---|

frame 5 |

_bfd_elf_gc_mark() |

.text.fun2 |

frame 4 |

_bfd_elf_gc_mark_reloc() |

.text.fun2 |

frame 3 |

_bfd_elf_gc_mark() |

.text.main |

frame 5 |

_bfd_elf_gc_mark_reloc() |

.text.main |

frame 1 |

_bfd_elf_gc_mark() |

.text |

ELF Relocation Entries

Through the analysis above, we now understand that linkers determine which other sections a function’s section references through relocation entries that are stored in the ELF file.

$readelf -r test.o

Relocation section '.rela.text.main' at offset 0x278 contains 2 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

00000000000a 000600000004 R_X86_64_PLT32 0000000000000000 fun1 - 4

000000000014 000700000004 R_X86_64_PLT32 0000000000000000 fun2 - 4

Relocation section '.rela.eh_frame' at offset 0x2a8 contains 4 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

000000000020 000200000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .text.fun1 + 0

000000000040 000300000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .text.fun2 + 0

000000000060 000400000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .text.un_used + 0

000000000080 000500000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .text.main + 0

From this command’s output, we can derive the following table:

| Sym. Name | Offset Hex | Offset Decimal |

|---|---|---|

fun1 |

00000000000a | 10 |

fun2 |

000000000014 | 20 |

These match the r_offset values of 10 and 20 found in the function call chain analysis, and the entries in .rela.text.main lack un_used. This indicates that the linker reads this part of the information to parse the reference relationships.

Conclusion

By studying how the linker links a simple program and analyzing it from the source code level, we have seen how the linker determines the references of one function’s section to other function sections when the --gc-sections option is enabled.

The linker parses and processes reference information from the relocation entries stored in the ELF file.

In fact, the linker does the same for global variables. The -fdata-sections option places each global variable in its separate .bss section. If fun1() uses a global variable used, the linker will parse the .bss.used section when traversing fun1()’s references.

References

- Tiny Linux Kernel Project: Section Garbage Collection Patchset

- Relocation - CSAPP

- Symbols and Symbol Tables - CSAPP