This article has been translated from Chinese by ChatGPT, and the wording may not be entirely accurate.

Addressing Linux Kernel Section GC Failure Issues - Part 1

Overview

This article is part of the Addressing Linux Kernel Section GC Failure Issues series.

- Section GC Analysis - Part 1 Introduction to the Principle

- Section GC Analysis - Part 2 Gold Source Code Analysis

- Section GC Analysis - Part 3 Reference Construction Process

- Addressing Linux Kernel Section GC Failure Issues - Part 1

- Addressing Linux Kernel Section GC Failure Issues - Part 2

The previous articles introduced the usage method and the principle of Section GC. Now let’s study the Section GC failure issue in the Linux kernel.

A linker can delete unused functions and variables when the --gc-sections option is enabled, because the ELF file format contains references to functions and variables, enabling the linker to establish dependencies between sections. If a function or variable is not referenced by any other function, then it can be deleted.

This article provides a detailed introduction to the reference building process.

If a section is created without a reference relationship, it becomes an orphan section and is garbage collected (GC) by default. The linker’s KEEP command can be used to forcibly retain such a section. There are many such sections in the Linux Kernel.

In reality, many of the forcibly retained sections could be GC’d. Is it possible to manually create references for these sections to cut out as much redundant code as possible? This series of articles aims to solve this problem.

Basic Usage of .pushsection

.pushsection is one of the assembly language directives widely used in the kernel. This syntax does not establish a reference relationship. Orphan sections are mainly created by it.

Below is a simple example using .pushsection:

// example.c

void fun() {

asm(".pushsection .rodata.test,\"a\"\n\t"

".string \"this_is_a_new_section\"\n\t"

".popsection\n");

}

int main() { fun(); }

Compile with the -ffunction-sections option to place sections in different areas, which makes it easier to delete them later.

Now let’s look at the compiled assembly to understand the role of .pushsection.

$ riscv64-linux-gnu-gcc -ffunction-sections example.c -S

$ cat example.s

.file "example.c"

.option pic

.text

.section .text.fun,"ax",@progbits

.align 1

.globl fun

.type fun, @function

fun:

addi sp,sp,-16

sd s0,8(sp)

addi s0,sp,16

#APP

# 2 "example.c" 1

.pushsection .rodata.test,"a"

.string "this_is_a_new_section"

.popsection

# 0 "" 2

#NO_APP

nop

ld s0,8(sp)

addi sp,sp,16

jr ra

.size fun, .-fun

.section .text.main,"ax",@progbits

.align 1

.globl main

.type main, @function

main:

addi sp,sp,-16

sd ra,8(sp)

sd s0,0(sp)

addi s0,sp,16

call fun

li a5,0

mv a0,a5

ld ra,8(sp)

ld s0,0(sp)

addi sp,sp,16

jr ra

.size main, .-main

.ident "GCC: (Ubuntu 11.4.0-1ubuntu1~22.04) 11.4.0"

.section .note.GNU-stack,"",@progbits

When compiling a C program, the compiler goes through several stages:

- Preprocessing Stage: Expand macros and includes in C language

- Compilation Stage: The compiler cc1 first converts the C language into compiler Intermediate Representation (IR), optimizes the program at the IR stage, then converts it into assembly according to the assembly syntax rules of the target architecture.

- Assembly Stage: The assembler translates the assembly code into machine code and generates an object file. An object file is a binary file that contains machine instructions for a specific platform but has not yet been linked into the final executable.

- Linkage Stage: The linker links the compiled object files with the required library files, resolves symbol references, and creates the final executable. In this stage, all function and variable references are resolved into memory addresses to produce a complete executable.

The final ELF executable is divided into different sections such as the code section .text and the data section .data. These sections are already divided during the compilation phase.

The assembler parses the assembly and recognizes .pushsection at which point it pauses processing the current section and creates a new one; when the assembler’s parsing identifies .popsection, the additional new section process is completed, and it resumes processing the previous paused section.

Viewing the Section Headers of the .o file:

$ riscv64-linux-gnu-gcc -ffunction-sections example.c -c

$ riscv64-linux-gnu-readelf -S example.o

There are 14 section headers, starting at offset 0x310:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000040

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 2

[ 2] .data PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000040

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 1

[ 3] .bss NOBITS 0000000000000000 00000040

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 1

[ 4] .text.fun PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000040

000000000000000e 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 2

[ 5] .rodata.test PROGBITS 0000000000000000 0000004e

0000000000000016 0000000000000000 A 0 0 1

[ 6] .text.main PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000064

000000000000001c 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 2

[ 7] .rela.text.main RELA 0000000000000000 00000260

0000000000000030 0000000000000018 I 11 6 8

[ 8] .comment PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000080

000000000000002c 0000000000000001 MS 0 0 1

[ 9] .note.GNU-stack PROGBITS 0000000000000000 000000ac

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[10] .riscv.attributes RISCV_ATTRIBUTE 0000000000000000 000000ac

0000000000000033 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[11] .symtab SYMTAB 0000000000000000 000000e0

0000000000000168 0000000000000018 12 13 8

[12] .strtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00000248

0000000000000017 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[13] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00000290

000000000000007e 0000000000000000 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

D (mbind), p (processor specific)

Key to Flags: W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info), L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS), C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude), D (mbind), p (processor specific)

As you can see, the `.rodata.test` section was generated by `.pushsection`.

Compiling example.c, checking the behavior of `.pushsection` with `--gc-sections` enabled:

$ riscv64-linux-gnu-gcc -ffunction-sections -Wl,–gc-sections,–print-gc-sections example.c ld: removing unused section ‘.rodata.cst4’ in file ‘/usr/riscv64-linux-gnu/usr/lib/Scrt1.o’ ld: removing unused section ‘.riscv.attributes’ in file ‘/usr/lib/gcc/riscv64-linux-gnu/12.2.0/crti.o’ ld: removing unused section ‘.rodata.test’ in file ‘/tmp/cceaBups.o’ ld: removing unused section ‘.riscv.attributes’ in file ‘/usr/lib/gcc/riscv64-linux-gnu/12.2.0/crtn.o’

The `.rodata.test` section was deleted as it was not referenced by any other section.

## Methods to Forcibly Retain Sections

Usually, if function A calls function B, then function A will reference function B, and the linker will traverse the reference relationship during garbage collection to retain referenced functions. However, since `.rodata.test` is created by `.pushsection` and does not create a reference relationship to other functions, it will be garbage collected.

This incorrect garbage collection can prevent the program from running correctly. We can use some directives to forcibly retain sections generated by `.pushsection`. The most common practice in the kernel is to use KEEP in the linking script. Also, other methods can forcibly retain sections.

Consulting the [documentation][005] for `as`, you can view the definitions of `.pushsection` and `.section`.

.pushsection name [, subsection] [, “flags”[, @type[,arguments]]] .section name [, “flags”[, @type[,flag_specific_arguments]]]

The `flags` contain one that meets our requirements:

R retained section (apply SHF_GNU_RETAIN to prevent linker garbage collection, GNU ELF extension)

After using this `flags`, there is no need to KEEP in the linking script, and the `.pushsection` created section will be retained in GC.

Example code:

.pushsection .rodata.test,”aR”,@progbits

Essentially, this method is no different from KEEP and cannot delete the redundant code, but it provides a line of thought for further research—the toolchain may have some options to manually establish references.

## Issues with .pushsection and Forcible Retention

The forcible retention methods mentioned in the previous section can cause some problems, which can be discussed in two cases.

1. Sections produced by `.pushsection` should not have been retained but were kept.

For example, a function `section_pusher()` used `.pushsection pushed_section` to add data to the `pushed_section`. If `section_pusher()` is deleted due to GC, then the `pushed_section` it created naturally should not be used elsewhere, but `pushed_section` is still forcibly retained.

2. `.pushsection` refers to `section_pusher()`, causing ownership inversion, and `section_pusher()` is also forcibly retained.

Below is an example of case 2:

```c

// example2.c

void section_pusher() {

asm("1: nop\n"

".pushsection pushed_section,\"aR\"\n\t"

".long ((1b) - .)\n\t"

".popsection\n");

}

int main() {

return 0;

}

$ riscv64-linux-gnu-gcc -ffunction-sections -Wl,--gc-sections,--print-gc-sections example2.c

ld: removing unused section '.rodata.cst4' in file '/usr/lib/gcc-cross/riscv64-linux-gnu/11/../../../../riscv64-linux-gnu/lib/Scrt1.o'

ld: removing unused section '.riscv.attributes' in file '/usr/lib/gcc-cross/riscv64-linux-gnu/11/crti.o'

ld: removing unused section '.riscv.attributes' in file '/usr/lib/gcc-cross/riscv64-linux-gnu/11/crtn.o'

In example2.c, .pushsection pushed_section,aR forcibly retains pushed_section using the R flag.

.long ((1b) - .) is an instruction used to calculate offsets. 1b refers to a previously defined label, indicating the address of label 1; . represents the current location’s address. Thus, (1b) - . computes the offset between the label 1 in fun() and the current position.

Here pushed_section refers to section_pusher(), making section_pusher() a subsection of pushed_section, forming an incorrect dependency. Not only will pushed_section be forcibly retained, but section_pusher() will also be kept.

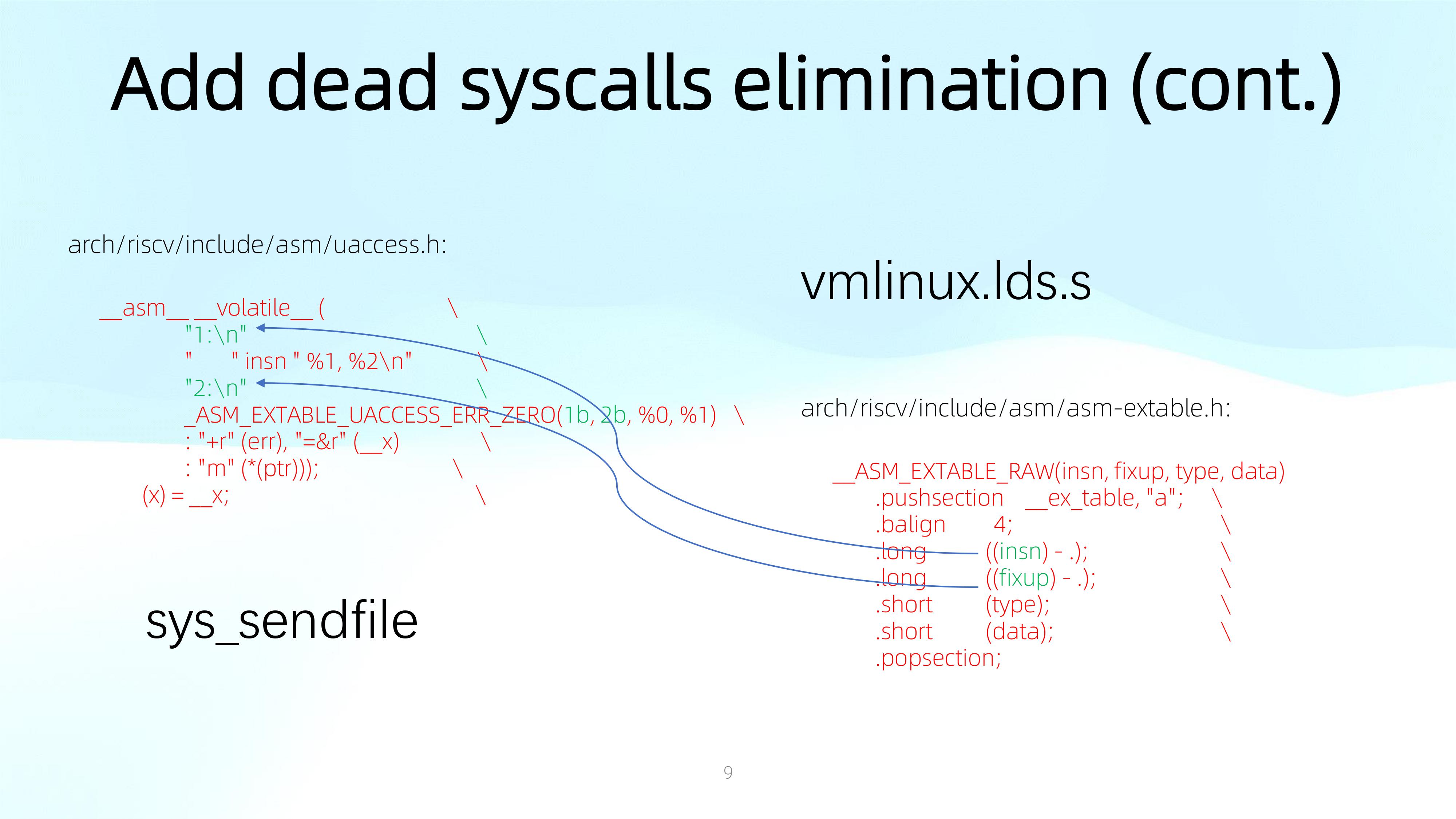

Introducing __ex_table

__ex_table is a data structure used for handling exceptions, and the exception table entries are defined like this:

// arch/riscv/include/asm/extable.h:18

struct exception_table_entry {

int insn, fixup; // Offsets to the instruction causing the exception and the exception handling code

short type, data;

};

An exception table differs from an exception vector table. The processor finds the corresponding exception handler in the exception vector table when an exception occurs. Exception handlers cannot distinguish some exception situations, so an exception table is used.

For a more detailed explanation of exception tables, please refer to the references cited later: 6, 7, 8.

__ex_table belongs to the second case mentioned before, where pushed_section refers to section_pusher().

The definition of __ex_table is as follows:

// arch/riscv/include/asm/asm-extable.h:14

#define __ASM_EXTABLE_RAW(insn, fixup, type, data) \

".pushsection __ex_table, \"a\"\n" \

".balign 4\n" \

".long ((" insn ") - .)\n" \

".long ((" fixup ") - .)\n" \

".short (" type ")\n" \

".short (" data ")\n" \

".popsection\n"

__ex_table refers to the parent section’s insn, fixup, type, data, making the parent section also be wrongly retained.

Conclusion

This article introduced the principles behind Section GC failure and .pushsection, with examples of .pushsection usage in the Linux Kernel.

In the following articles, we will explore methods for establishing correct references for .pushsection.